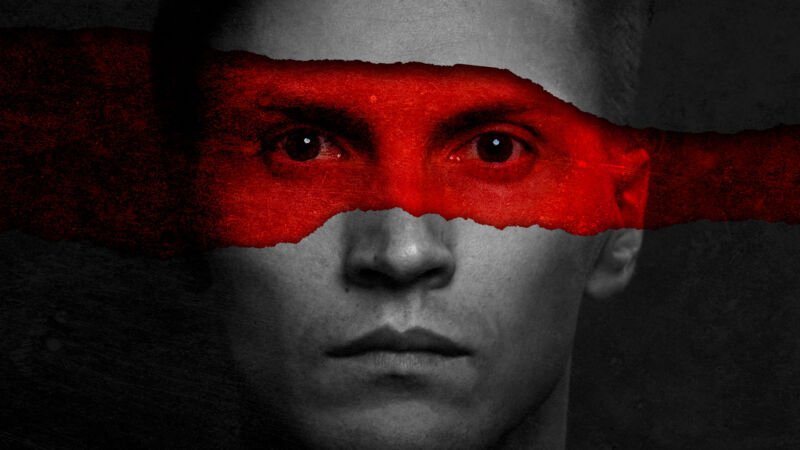

Aurich Lawson | Getty Images

Think of a psychopath and you could think of any number of Hollywood villains, from handsome killers like Hannibal Lecter to Anton Chigurh, played with chilling menace by Javier Bardem in the film It’s no country for old men. But the traits and symptoms of psychopathy run along scales from weak to strong. Thus, someone can be mildly psychopathic or severely psychopathic. There may be a psychopath sitting next to you right now.

Some psychologists argue that the focus on violent and criminal psychopathic behavior has marginalized the study of what they call successful psychopaths, people who have psychopathic tendencies but can stay out of trouble and perhaps even take advantage of these traits in some way. Researchers haven’t yet reached a consensus on what traits distinguish successful psychopaths from serial killers, but they’re working to clarify what they say is a misunderstood branch of human behavior. Some even want to reclaim and rehabilitate the very concept of psychopathy.

Most of what people think about psychopaths isn’t what psychopathy really is, says Louise Wallace, a professor of forensic psychology at the University of Derby, England. It’s not glamorous. It’s not a show. Psychopathic traits exist in everyone to some extent and shouldn’t be glorified or stigmatized, she says.

In a sense, the study of successful psychopaths brings the field back to the beginning. In his 1941 book,The mask of sanitythe influential US psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley outlined the personality profile of a psychopath: a seemingly charming but self-centered and unreliable person who hides an antisocial core.

Cleckley (who later identified notorious serial killer Ted Bundy as a psychopath) drew his insights from people he saw in psychiatric centers. Among his descriptions of psychopaths were people who could keep the worst of their behavior at bay. He sketched a profile of a psychopathic businessman, for example, who worked hard and seemed normal except for bouts of marital infidelity, callousness, binge drinking and risk-taking.

In the decades that followed, researchers who wanted to study psychopathy often did so in prisons. And so, fueled by horrific portrayals in books and films, the psychopathic profile originally envisioned more broadly by Cleckley has become closely associated with dangerous and violent criminals in both the public and academic spheres.

This point of view is now being challenged. In the last 15 years or so, psychiatry has embraced what is called a dimensional approach, based on the idea of scales and spectrums of severity of traits and symptoms. This replaced the categorical approach, which took a more binary view of mental syndromes and assessed whether or not the conditions were present.

Seeing psychopathy through this different lens has opened new doors for researchers. They no longer needed to work in prisons to study psychopathy. Instead, they could recruit groups from the general population, screen them for psychopathic traits, and investigate the behavior and biology of normal people with successful or mild psychopathy. Most psychopathic individuals live around us, says Dsir Palmen, a clinical psychology researcher at Avans University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands.

Balanced by boldness

Psychopathy is a composite of several interacting traits. The traditional model of a psychopathic mind focuses on meanness and disinhibition. In psychological terms, meanness is an aggressive pursuit of resources with no regard for others. Disinhibition manifests itself as a lack of impulse control. People tall in both traits feel little or no empathy and find it difficult to control their actions, often with violent consequences.

As part of the recent rethink, psychologists have introduced a new factor: boldness, which they define as a mix of social dominance, emotional resilience, and adventurousness.

You can think of boldness as courage expressed in the realm of interactions with other people where you’re not easily intimidated, you’re more assertive, even dominant with other people, says longtime psychopathy researcher Christopher Patrick, a clinical psychologist at Florida State University, which highlighted the role of boldness in a 2022 article on psychopathy in the Annual Review of Clinical Psychology.

A bold person isn’t necessarily a psychopath, of course. But add boldness to high degrees of meanness and uninhibitedness, Patrick says, and you might have a psychopath who is more capable of using their social confidence to mask the extremes of their behavior and thus excel in positions of leadership. Indeed, it may be that the degree of boldness is closely related to whether someone with traditionally psychopathic traits can make their life a success.

Other psychopathic traits can also benefit people in certain careers: meanness, for example, often manifests itself as a lack of empathy. Within the corporate world, you want someone who can perform under pressure and make quick decisions, perhaps without displaying high levels of empathy, because they need to be able to make those ruthless choices, says Wallace.

A 2016 study of Australian advertising agency employees, for example, found that senior executives scored higher than younger staff on measures of behaviors related to psychopathic traits such as being initially charming, level-headed, and calm, but also self-centered, ruthless and lacking in self-blame.

Other research has suggested that the language used to describe the ideal candidate in executive job postings may actively attract candidates with psychopathic traits. In one particularly direct example, a British company advertised in 2016 for a New Business Media sales executive psychopathic superstar! 50 thousand 110 thousand. The ad stated that one in five CEOs was a psychopath and wanted a candidate with the positive qualities of him.

Some have even suggested that psychopathic traits and associated tendencies like courage and narcissism can make people act heroic. A 2018 study, for example, suggested that first responders scored significantly higher than civilians on measures of psychopathy, including fearless dominance, boldness, and sensation-seeking.

The idea that some psychopathic traits can be good doesn’t sit well with everyone. There’s been a big, big battle over this, says Klaus J. Templer, an organizational psychology consultant formerly of the Singapore University of Social Sciences.

Critics dispute the inclusion of boldness as a defining psychopathic trait, Templer says. A 2021 study asked more than 1,000 students to agree or disagree with statements to probe for traits including meanness (I don’t care if someone I don’t like gets hurt), disinhibition (I took money out of my purse or from someone’s wallet without asking) and boldness ( I’m a born leader).

The findings suggested that increased levels of meanness and disinhibition could explain the variance in self-reported antisocial behaviors, such as aggression, rule breaking and drug use. In other words, audacity was largely irrelevant.

But Patrick thinks some people don’t fit that interpretation. Other research has identified people who score higher than most on meanness or disinhibition, but who don’t seem to get in trouble for antisocial behavior. Boldness can make a difference: Some studies suggest that boldness can be protective in terms of well-being and behavior in the workplace.

They would find it easier to chat with people and use people and so on, says Patrick. This type of successful psychopath can turn out to be completely unreliable, but initially comes across as assertive and capable, he adds. This is what audacity brings to the table.

Much of this academic debate is a legacy of the reliance on studying people who have committed violent or criminal acts to evaluate and diagnose psychopathy, Wallace says. Once psychopathy is labeled as a clinical disorder characterized by extreme violence, then all positive adaptive traits are set aside, he says. And now the researchers are just going back on themselves a little bit and saying, wait, how about all this good stuff.

Part of the problem, he says, is that researchers trying to study the positive traits of psychopathy don’t have their own version of the screening tool used to identify the most severe cases. This is a checklist focusing on the effects of disinhibition and meanness developed by Canadian psychologist Robert Hare and immortalized in the 2011 book The psychopath test by Jon Ronson.

To fill this gap, Wallace helped produce the Psychopathy Achievement Scale: a 54-item scale designed to identify and rate psychopathic traits in the general population. He hopes the scale, currently under review in the Journal of Personality Assessment, will help researchers in the field assess, for example, the prevalence of successful workplace psychopathy or psychopathic traits in people in positions of power and leadership. . The scale asks respondents whether they agree with statements such as Achieving success can be difficult; it’s all about survival of the fittest.

I think scale is needed, because successful psychopathy research at the moment is almost like fumbling in the dark, she says. The only way you can actually carry out research is to be able to measure these traits.

Ultimately, Wallace hopes the scale will help more people realize that a person with psychopathic traits isn’t always something to be afraid of. There’s so much we don’t know about individuals who have high prototypical psychopathic traits and how they just engage with their day-to-day lives, he says. And that’s because we got lost in this Hannibal Lecter idea.

Knowable Magazine, 2023. DOI: 10.1146/knowable-071923-2 (DOI information)

David Adam is an author and journalist in London. This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, an independent reporting effort of Annual Reviews. Subscribe to the newsletter.

#upsides #psychopath #Ars #Technique

Image Source : arstechnica.com