By Fred Clasen-Kelly

KFF health news

Bridget Narsh’s son Mason needed urgent help in January 2020, so she was offered the option of sending him to Central Regional Hospital, a state mental health facility in Butner, North Carolina.

The teenager, who deals with autism and PTSD and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, had started destroying furniture and running away from home. Her mother was concerned for the safety of Mason and the rest of the family.

But kids in crisis in North Carolina can wait weeks or months for a psychiatric bed because the state doesn’t have the services to meet the demand. And when seats become available, they’re expensive.

The standard rate at Central Regional was $1,338 a day, which Narsh could not afford. So when a patient relations rep offered a discounted rate of less than $60 a day, her husband, Nathan, signed a deal.

Mason, now 17, was hospitalized for more than 100 days in the Central Regional in two separate stays that year, the documents show.

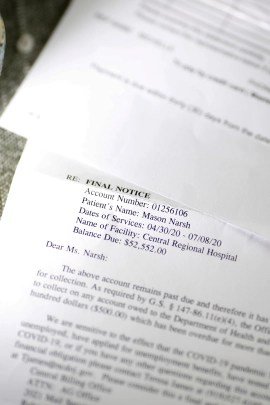

But when requests for payment came in the following year, Narsh said she was shocked. The letters, which were marked final notice and requiring immediate payment, were signed by a paralegal in the office of Josh Stein, North Carolina Attorney General. The total bill, $101,546.49, was significantly more than the approximately $6,700 the Narshes expected to pay under their agreement with the hospital.

I had to tell myself to keep calm, said Bridget Narsh, 44, who lives with her husband and three children in Chapel Hill. There is no way I can pay for this.

Medical bills have disrupted the lives of millions of Americans, with hospitals burdening homes and driving many into bankruptcy. In recent years, lawmakers have railed against privately-run hospitals, and states have passed laws intended to make medical billing more transparent and limit aggressive debt collection tactics.

Some state attorneys general as senior law enforcement officials in their state have pursued efforts to protect residents from harmful billing and debt collection practices. But in the name of protecting taxpayer assets, their offices are also often responsible for collecting unpaid debts for state facilities, which can put them in a contradictory position.

Stein, a Democrat running for governor in 2024, made hospital consolidation and healthcare pricing transparency a key issue during his tenure.

I have real concerns about this trend, Stein said in 2021 of the surge in hospital consolidations across the states. Hospital system pricing is closely related to this issue, as consolidations drive up already excessive healthcare costs.

Stein declined a request to be interviewed about Masons’ accounts, which came in late 2021 because the North Carolina government put its debt collection on hold in March 2020 as the nation felt the economic fallout from the covid-19 pandemic.

Across the nation, states seize money or assets, file lawsuits, or take other steps to collect debts from people residing in state hospitals and other institutions, and their efforts can disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minorities and the poor, according to health care consumer advocates. In North Carolina, officials seeking to collect unpaid debts are allowed to garnish income tax refunds of residents.

Attorneys general must balance their traditional role of protecting consumers from harmful debt collection practices and the state’s obligation to serve taxpayer interests and fund services, said Vikas Saini, a cardiologist and president of the Lown Institute, a Massachusetts-based nonpartisan think tank that advocates for health care reform.

The Narsh case is the perfect storm of every problem in our healthcare system, said Saini, who at the request of KFF Health News reviewed the payment demand letters received from the family. Too often, health care is inaccessible, billing is not transparent, and patients end up facing huge financial burdens because they or a loved one is ill, Saini said.

The Narsh family had Blue Cross and Blue Shield health insurance at the time of Mason’s hospitalizations. Bridget Narsh has documents showing the insurance paid about $7,200 for one of her stays. (Mason is now covered by Medicaid, the federal state health insurance that covers some people with disabilities and those on low incomes.)

In a written statement, Nazneen Ahmed, a spokeswoman for Steins’ office, said state law requires most agencies to submit their unpaid debts to the state Department of Justice, which is responsible for contacting individuals who may be in debt.

Ahmed ran KFF Health News at the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees Central Regional Hospital.

Bailey Pennington Allison, an agency spokesperson, said in a written statement that officials researched the Narsh case and determined the state had followed proper procedures for billing the family.

The state bases its rates for services on the costs of treatment, nursing, career counseling, hospital room, meals and laundry, Pennington Allison said. Hospital staff then work with patients and families to learn about their income and resources to determine what they can afford and how much they will be charged, she said.

The spokesperson didn’t explain why Mason’s parents were offered, but ultimately didn’t receive, a discounted rate both times he was admitted in 2020.

Narsh contacted an attorney, who negotiated the bill with the state. In April, her family reached an agreement with North Carolina officials to pay $100 a month in exchange for the state cutting spending by about 96 percent to about $4,300. If Narsh defaults, however, the settlement stipulates that he must come up with the original total.

States can take a variety of approaches to debt collection. North Carolina is one of about a dozen that can give residents income tax refunds, said Richard Gundling, senior vice president of the Healthcare Financial Management Association, a membership organization for finance professionals.

Gundling said state officials have a responsibility to protect taxpayers’ money and collect what’s owed, but that the seizure of tax returns can have more serious consequences for people on lower incomes. There is a balance that must be struck to be reasonable, he said she.

With health care a leading cause of personal debt, unpaid medical bills have become a major political issue in North Carolina.

State lawmakers are considering a bill called the Medical Debt De-Weaponization Act, which would limit the ability of debt collectors to engage in extraordinary collections such as foreclosing a patient’s home or garnishing wages. But the current version of the bill would not apply to state health care facilities like the one Mason Narsh went to, according to Pennington Allison.

In a written statement, Stein said he supports legislative efforts to strengthen consumer protections.

Every North Carolina should be able to get the health care it needs without becoming overwhelmed with debt, Stein said. You called the bill under consideration a step in the right direction.

Narsh said the unexpectedly large bill was frustrating, at least in part because she’s struggled for years to get more affordable preventative care for Mason in North Carolina. Narsh said she is having difficulty finding services for people with behavioral problems, a shortage acknowledged in a state report released last year.

Several times, she said, she was left with no choice but to take him to a hospital to be evaluated and placed in an inpatient mental health facility not suited to people with complex needs.

Sign up to our newsletter

“*” Indicates required fields

Community-based services that allow people to get treatment at home can help them avoid the need for mental hospitals in the first place, Narsh said. Mason’s condition improved after he received a service dog trained to help people with autism, among other community services, Narsh says.

Corye Dunn is the director of public policy at Disability Rights North Carolina, a Raleigh-based nonprofit contracted by the federal government to monitor public facilities and services to protect people with disabilities from abuse. The irony, she said, is that the same system that is ill-equipped to keep people from falling into slumps can then come after them with big bills.

This is bad public order. This is bad health care, Dunn said.

#mom #owed #hospital #care #Josh #Steins #office #told #pay

Image Source : www.northcarolinahealthnews.org